AUDIO PODCAST OPTION OF LION KING 2019 TAKES ITS RIGHTFUL PLACE ON THE THRONE

SHORT TAKE:

Put this in the column of WELL done, and astonishingly realistic, live action remakes of a classic Disney animated movie.

WHO SHOULD GO:

Anyone – though, for a kid movie, the subjects of fratricide, murderous hyenas, and fights to the death might (and did in the showing I went to) upset the younger kids. That’s going to have to be a parental call on a kid by kid basis. There were certainly scenes in this one which were even harder to watch than in the animated movie because of the VERY life-like CGI.

LONG TAKE:

SPOILERS BUT ONLY FOR THOSE 3 OR 4 PEOPLE IN THE SOLAR SYSTEM OVER 10 WHO HAVE NOT SEEN THE ORIGINAL ANIMATED VERSION

Chalk another one up for The Mouse. Before I launch into my review, I’ll say it right now, the CGI IS ASTONISHING. It’s actually just a teensy bit frightening how authentically film makers can now manufacture real life. The animals seem very very life-like.

Aside from allowing the animals to speak, the director, Jon Favreau has had the animators keep the facial and body movement as close as possible to the authentic musculature of real animals, including, of course, their limitations.

Aside from allowing the animals to speak, the director, Jon Favreau has had the animators keep the facial and body movement as close as possible to the authentic musculature of real animals, including, of course, their limitations.  Real animals don’t smile. Real animals can’t manipulate things which require an opposable digit — unless they have an opposable digit. Real animals don’t dance or pull hula skirts out of thin air.

Real animals don’t smile. Real animals can’t manipulate things which require an opposable digit — unless they have an opposable digit. Real animals don’t dance or pull hula skirts out of thin air.  Favreau’s team respects these natural and inherent limitations, bringing an added reality to the characters which was different from the animated version. Audiences generally allow an extra layer of suspension of disbelief not usually afforded a live action and Favreau’s team obviously kept that in mind – creatively working within those limits, making the almost athletically energetic vocals of the human actors all that more important to achieve. And achieve those goals they do.

Favreau’s team respects these natural and inherent limitations, bringing an added reality to the characters which was different from the animated version. Audiences generally allow an extra layer of suspension of disbelief not usually afforded a live action and Favreau’s team obviously kept that in mind – creatively working within those limits, making the almost athletically energetic vocals of the human actors all that more important to achieve. And achieve those goals they do.

Despite the early reviews which did not have a lot of love for the (then) upcoming 2019 Lion King, this one deserved all the (literal) applause it got during the credits. I’ll admit to some trepidation, as while Aladdin was well done, Dumbo was an overblown flop. And as Lion King is one of their most enduring and intelligently created stories, I had some reservations.

Despite the early reviews which did not have a lot of love for the (then) upcoming 2019 Lion King, this one deserved all the (literal) applause it got during the credits. I’ll admit to some trepidation, as while Aladdin was well done, Dumbo was an overblown flop. And as Lion King is one of their most enduring and intelligently created stories, I had some reservations.  But from the opening scenes I was enchanted.

But from the opening scenes I was enchanted.

The entire original animated story is there, as this live action tracks about 90% of the original animated version scene for scene and image for image, notable from the opening sequence as the animals gather to welcome the newly born Prince Simba. The only notable differences throughout the 2019 version were that some of the quips were missing and some of the more ridiculous slapstick was excised. For example, and in keeping with the aforementioned recognition of the natural limitations of real animals: Zazu was not left under a pile of rhinoceroses as cubs Simba and Nala escape his watchful eye, and  Timon did not don a hula skirt as a distraction for the hyenas just before the climactic battle. (Do I know the original well? With 6 kids, I have probably seen this movie over a dozen times, so yes.)

Timon did not don a hula skirt as a distraction for the hyenas just before the climactic battle. (Do I know the original well? With 6 kids, I have probably seen this movie over a dozen times, so yes.)

Only one scene, in my analysis, suffered slightly from lack of (if you’ll excuse the pun) impact in a diversion from the original. When Rafiki counsels Simba to return to his pride, in the original animated version Rafiki whacks Simba on the head with his club to make the point that: Yes, some history is painful, but once endured, it is then in the past and must be overcome in order to move forward.

Only one scene, in my analysis, suffered slightly from lack of (if you’ll excuse the pun) impact in a diversion from the original. When Rafiki counsels Simba to return to his pride, in the original animated version Rafiki whacks Simba on the head with his club to make the point that: Yes, some history is painful, but once endured, it is then in the past and must be overcome in order to move forward.  I can think of some stupid PC reasons why they did not include this part of Rafiki’s argument, but maybe they had a legit plot consideration. In any event this scene is not used in Rafiki’s counsel to Simba in the 2019 version.

I can think of some stupid PC reasons why they did not include this part of Rafiki’s argument, but maybe they had a legit plot consideration. In any event this scene is not used in Rafiki’s counsel to Simba in the 2019 version.

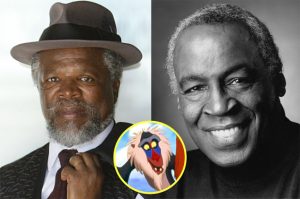

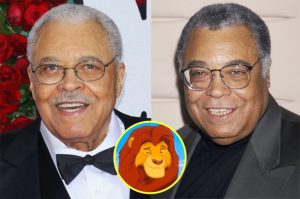

Along with why this scene and some of the more memorable quotes were not included, another thing the film makers do not explain is their casting choices. Of the main cast:  James Earl Jones who majestically voiced Mufasa,

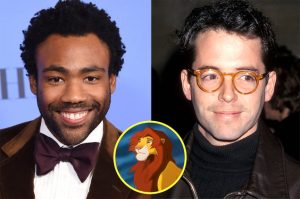

James Earl Jones who majestically voiced Mufasa,  Matthew Broderick who played Simba,

Matthew Broderick who played Simba,  Madge Sinclair who voiced Sarabi,

Madge Sinclair who voiced Sarabi,  Robert Guillame who charmingly gave life to Rafiki,

Robert Guillame who charmingly gave life to Rafiki,  Jeremy Irons who chillingly voiced Scar,

Jeremy Irons who chillingly voiced Scar,  Nathan Lane and

Nathan Lane and  Ernie Sabella, who stole every scene they were in as the comic duo of Timon and Pumbaa,

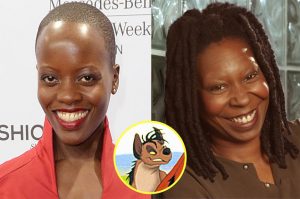

Ernie Sabella, who stole every scene they were in as the comic duo of Timon and Pumbaa,  Cheech Marin and Whoopi Goldberg who lent their comic talents to the hyenas, and

Cheech Marin and Whoopi Goldberg who lent their comic talents to the hyenas, and  Rowen Atkinson whose brilliant dry wit was conveyed into Zazu,

Rowen Atkinson whose brilliant dry wit was conveyed into Zazu,  Jones was the only actor asked back.

Jones was the only actor asked back.

There was some ink spilled in the media effusing about how Jones links the movie back to the traditional version and I, personally, was delighted to have him revisit the voice of Mufasa. He has all the timbre of the majestic leader plus his age adds a wonderful, almost foreboding to his character. But I could find very little info on why they did not call the entire cast back. Aside from the tragic death of Guillame, taken by cancer in 2017, and Madge Sinclair who passed away from leukemia not long after The Lion King came out, all of the performers are not only still alive but still active and have ongoing projects.  And, aside from the child actor voices from whom replacement by JD McCrary and Shahadi Wright Joseph is understandable, as they now will obviously sound too old for those roles, when acting the adult characters, the ages are irrelevant since they are all doing vocal performances.

And, aside from the child actor voices from whom replacement by JD McCrary and Shahadi Wright Joseph is understandable, as they now will obviously sound too old for those roles, when acting the adult characters, the ages are irrelevant since they are all doing vocal performances.

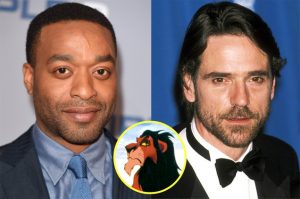

The only info I could get on the casting issue was in an interview with Jeremy Irons. When asked why he did not reprise his role as Scar in the new version all he could say was: They didn’t ask me. He then, graciously and diplomatically went on to praise the choice of Chiwetel Ejiofor .

There is NOTHING wrong with the performances in the movie, and had they been the first ones I heard doing these roles I could have been quite content. BUT having heard Broderick, Atkinson, Irons, etc in their respective roles, it was a constant distraction to actively miss the original cast, especially when Jones’ terrific performance was a continuous reminder that the others were not there.

There is NOTHING wrong with the performances in the movie, and had they been the first ones I heard doing these roles I could have been quite content. BUT having heard Broderick, Atkinson, Irons, etc in their respective roles, it was a constant distraction to actively miss the original cast, especially when Jones’ terrific performance was a continuous reminder that the others were not there.

But don’t let my complaints dissuade you from the movie.  Despite the differences, I thought this a very well done version. I am merely expressing an, admitted, bias for the details about the one our kids grew up with. I understand some of the changes omitting the more obvious cartoonish slapstick but while I do not understand some of the other choices, can accept them as not being in this version’s vision.

Despite the differences, I thought this a very well done version. I am merely expressing an, admitted, bias for the details about the one our kids grew up with. I understand some of the changes omitting the more obvious cartoonish slapstick but while I do not understand some of the other choices, can accept them as not being in this version’s vision.

Chiwetel Ejiofor (2012, Dr. Strange and Children of Men) takes on Scar.

Chiwetel Ejiofor (2012, Dr. Strange and Children of Men) takes on Scar.  Donald Glover (The Martian, Solo and Spider-Man : Homecoming) takes over for Simba. John Oliver voices Zazu.

Donald Glover (The Martian, Solo and Spider-Man : Homecoming) takes over for Simba. John Oliver voices Zazu.  Alfre Woodard (Star Trek: First Contact, Captain America: Civil War) speaks for Sarabi. Seth Rogen and Billy Eichner carry

Alfre Woodard (Star Trek: First Contact, Captain America: Civil War) speaks for Sarabi. Seth Rogen and Billy Eichner carry  Pumbaa and Timon on their respective vocal backs, for which director Favreau wisely arranged for extended improv sessions, much like what was allowed for Lane and Sabella by directors Rogers Allers, and Rob Minkoff for the original, some of which lines were added to the final script.

Pumbaa and Timon on their respective vocal backs, for which director Favreau wisely arranged for extended improv sessions, much like what was allowed for Lane and Sabella by directors Rogers Allers, and Rob Minkoff for the original, some of which lines were added to the final script.

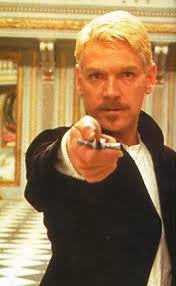

The Lion King, is heavily influenced by the story of Hamlet. For those not familiar with that theatrical acme,  Hamlet is a young prince who must overcome his own insecurities, immaturity and indecisiveness when faced with the prospect of leading his people, after his uncle secretly kills his father, making it appear to be an accident, and marries his mother. (Plug here: BEST Hamlet ever – and ONLY one, to date filmed in its entirety – best of my knowledge – is Branagh’s which you can buy or rent from Amazon – HERE.)

Hamlet is a young prince who must overcome his own insecurities, immaturity and indecisiveness when faced with the prospect of leading his people, after his uncle secretly kills his father, making it appear to be an accident, and marries his mother. (Plug here: BEST Hamlet ever – and ONLY one, to date filmed in its entirety – best of my knowledge – is Branagh’s which you can buy or rent from Amazon – HERE.)

A couple of decisions brings the newer version closer to the 500 year old play. As an example, the original Lion King defined Uncle Scar as grasping only for the crown.  This 2019 interpretation hits a bit closer to the Shakespearean home, referring to a past wherein Scar fought to take Sarabi as his queen and lost to Mufasa. But, unlike Hamlet’s mother, Sarabi has a bit more sense and turns Scar down. This interaction adds more texture to the plot and depth to the character of Scar.

This 2019 interpretation hits a bit closer to the Shakespearean home, referring to a past wherein Scar fought to take Sarabi as his queen and lost to Mufasa. But, unlike Hamlet’s mother, Sarabi has a bit more sense and turns Scar down. This interaction adds more texture to the plot and depth to the character of Scar.

Jon Favreau takes on the daunting task of bringing to life a new version of a beloved classic. Favreau is a very gifted and talented film maker. Favreau is responsible as a director for Iron Man 1 and 2, Jungle Book live action 1 and (the future) 2, an Orville episode, Cowboys and Aliens, Chef, and Zathura: A Space Adventure. He was producer for, among others, Avengers: Endgame and Infinity War. And his long list of acting credits include: creating the adorable sidekick to Iron Man, Happy Hogan, whose character arc has matured with the Avengers movies, as well as playing the titular character in the movie he both wrote and directed in Chef.

As a short digression, and in a lovely taste of poetic symmetry,  Favreau, as Happy Hogan, plays his own kind of Rafiki to Tom Holland’s Peter Parker in Spider-Man: Far From Home, counseling the young “Prince” to assume the mantle left for him by his de facto father, Stark, just the way Rafiki counsels Simba in Lion King.

Favreau, as Happy Hogan, plays his own kind of Rafiki to Tom Holland’s Peter Parker in Spider-Man: Far From Home, counseling the young “Prince” to assume the mantle left for him by his de facto father, Stark, just the way Rafiki counsels Simba in Lion King.

Hans Zimmer returns to refresh the soundtrack he composed for the original Lion King.  There are also a couple of additional songs, one of which is performed by Beyonce (who voices Nala) called “Spirit”. While the Shakesperean influence in Lion King, as I have already explained, is obvious, this 2019 versions also draws from the Biblical story of Moses, who went into exile, crossing the desert to spend years away, only to be called back to bring his people out of bondage.

There are also a couple of additional songs, one of which is performed by Beyonce (who voices Nala) called “Spirit”. While the Shakesperean influence in Lion King, as I have already explained, is obvious, this 2019 versions also draws from the Biblical story of Moses, who went into exile, crossing the desert to spend years away, only to be called back to bring his people out of bondage.  Similarly, Simba crosses the desert that separates his kingdom from the idyllic forest into which he is adopted, until, like Moses, upon his coming to maturity, is called to overcome his own fears and doubts and return – again back across the very Biblically symbolic desert – to free his people from the slavery of Scar and his hyenas. Emphasizing this connection is lyrics from Beyonce’s “Spirit” which includes the line: “So go into that far off land, and be one with the Great I Am, I Am….” The reference to God, the Great I Am, is unmistakably reverent to the Book of Genesis. This was an added depth to the story I hadn’t anticipated but admire about this new version very much.

Similarly, Simba crosses the desert that separates his kingdom from the idyllic forest into which he is adopted, until, like Moses, upon his coming to maturity, is called to overcome his own fears and doubts and return – again back across the very Biblically symbolic desert – to free his people from the slavery of Scar and his hyenas. Emphasizing this connection is lyrics from Beyonce’s “Spirit” which includes the line: “So go into that far off land, and be one with the Great I Am, I Am….” The reference to God, the Great I Am, is unmistakably reverent to the Book of Genesis. This was an added depth to the story I hadn’t anticipated but admire about this new version very much.

So go see the new Lion King. But to be fair to this lovely outing, see it with the fresh eyes that Jon Favreau and company have given it.