MASSIVE SPOILERS – WE’RE PRIMARILY DISCUSSING ENDINGS – SO YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!!!

ALTERNATE ENDINGS TO OLD CLASSICS!!!

I hate to disabuse you of an illusion but:

Classic movies are not written in stone.

Nonetheless, every movie buff prides themselves on knowing the endings to their favorite old movies. Even a casual connoisseur at the cinematic buffet might know or recognize last lines to a famous movie they haven’t even seen!

“T’was beauty killed the beast” (King Kong); “Frankly my dear I don’t give a damn” and “Tomorrow is another day.” (Two of the last few lines in Gone With the Wind), “There’s no place like home.” (The Wizard of Oz), “Top of the world, Ma.” (White Heat).

Phrases like these and the endings they invoke have inveigled their way into the cultural vocabulary so firmly one would think that all celluloid masterpieces have amaranthine finales , unlike today’s market driven and screen tested denouements with roundtable action figure consideration, directors’ cuts, and DVD special edition options.

But you’d be wrong. Even movies decades old, but still popular today, occasionally went through rewrites for a variety of reasons. These are some of my favorites.

AGAIN – SPOILERS!!! LAST WARNING!

Our Town

This 1940 beauty was originally a famous play by Thornton Wilder about small town Americana life at the turn of the century, mostly focusing on the relationship of childhood sweethearts George and Emily. In the stageplay, Emily dies in childbirth. In the movie she lives. Thornton Wilder explained his approval of this change when the play transitioned to film. He said the theater piece is understood as an abstract so there is a certain emotional distance between the characters and the audience. But in the cinema there is a closeness to reality, an intimacy and familiarity developed between the movie patrons and the big screen personas, which would have made Emily’s death just cruel, so when the producers approached him to change it – he agreed.

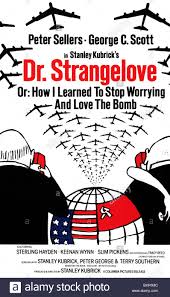

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Stanley Kubrick was known as both a brilliant cinematographer and an insufferably frustrating director. Infamous for telling his actors what he did not like, but notoriously stubborn in refusing to give them a clue as to what it was that he wanted, the filmatic and box office results were of checkerboard quality.

Anecdotes abound of Kubrick’s poor judgement as a director. Shelly Duvall broke down during filming of The Shining after a record approaching 127 takes of an intensely emotional scene. Kubrick routinely abused his cast to create a movie that even Stephen King, author of the source material, publicly stated he did not like, and who described it as: “…a big, beautiful Cadillac with no engine inside it.”

Stultifyingly long scenes in Barry Lyndon, where performers appeared afraid to move, resulted in that massive flop being appropriately nicknamed “Bore-y Lyndon”.

But in 1964’s wild ride, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Kubrick was both great cinematographer and great director. With talents like  George C. Scott,

George C. Scott,  Peter Sellers (who almost died from exhaustion playing three key roles),

Peter Sellers (who almost died from exhaustion playing three key roles),  Keenan Wynn and

Keenan Wynn and  Slim Pickens invigorating the set, it is understandable that this deeply dark satire on a world teetering on the edge of global nuclear war would click along with the bizarre uniqueness of Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits, while still evoking the cautionary thoughtfulness of Fail Safe, which Strangelove was parodying.

Slim Pickens invigorating the set, it is understandable that this deeply dark satire on a world teetering on the edge of global nuclear war would click along with the bizarre uniqueness of Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits, while still evoking the cautionary thoughtfulness of Fail Safe, which Strangelove was parodying.

The theatrically released ending sees the world committed to all inclusive radiated destruction, a plan for a handful of survivors to go underground with LOTS of extra buxom females with which to eventually – ahem – repopulate the Earth, and a previously wheelchair bound former Nazi scientist of questionable sanity, the eponymous Dr. Strangelove himself, rising unexpectedly from his chair, give the Nazi salute and shout:  “Mien Fuhrer, I can WALK!”

“Mien Fuhrer, I can WALK!”

As provocative, quirky, memorable and blackly funny as this is…this WASN’T the original ending. It was supposed to have gone on for another 5 minutes with – of all things – a PIE fight in the war room amongst the President, his cabinet heads, military leaders and the Russian ambassador!  However, with the assassination of JFK taking place as they were filming, the idea of a President being hit with anything was, wisely, determined to be a bit too close to the knuckle. On top of that the actors were having WAY too much fun throwing pies at each other to convey the bleak analogy for war Kubrick had intended.

However, with the assassination of JFK taking place as they were filming, the idea of a President being hit with anything was, wisely, determined to be a bit too close to the knuckle. On top of that the actors were having WAY too much fun throwing pies at each other to convey the bleak analogy for war Kubrick had intended.  So the scenes were set aside for later editing and simply….lost.

So the scenes were set aside for later editing and simply….lost.

The Birds

Then there is Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 bizarre alternate reality horror movie about birds in Bodega Bay, which suddenly and for no apparent or explained reason, flock by the hundreds to commit sudden and lethal suicide attacks on people, resulting in fatal and gruesome “peckings” as car windows are shattered, gas stations are blown up, and people are driven mad by the clawing, poking, feathered beasts.

In the theatrical ending the main protagonists drive slowly away from the decimated town, watched by hundreds, if not thousands of birds perched ominously on rooftops and telephone wires.

In the theatrical ending the main protagonists drive slowly away from the decimated town, watched by hundreds, if not thousands of birds perched ominously on rooftops and telephone wires.

However, Hitchcock’s initial vision ended the story with a scene showing the Golden Gate Bridge covered in birds, hinting at the world wide spread of this cataclysm. BUT lacking the CGI of today, the shocking implications of nature gone – well – wild, was left limited mysteriously to Bodega Bay, as the more spectacular visuals would have been prohibitively expensive, and therefore ended up … at the bottom of the bird cage.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

This brilliant view into the emotionally wrenching family dynamics of a Southern patriarchy is the most complicated in this list, as, though the changes of the Broadway endings are thin and slight, they are pregnant (if you’ll excuse the pun given the plot of COAHTR) each with complexly nuanced different meanings.

The story of Tennessee Williams’ most well known dysfunctional love/hate family actually has FOUR endings, albeit all similar but differing in key subtleties.

COAHTR centers around the relationship between young couple, Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor) and Brick (Paul Newman), at the birthday party for Big Daddy (Burl Ives), the wealthy head of a family whose interactions are strained, to say the least. Brick and “Gooper” (Jack Carson) are Big Daddy’s sons, who, like Esau and Issac, could not be more different. Gooper is the diligent, anxious to pleased progeny, whose demonstrably fertile wife’s child production is aimed at impressing Big Daddy into handing the dynasty on to her own husband.

Brick, formerly the fair haired boy and once favorite son, is now a broken down, alcoholic, ex-athlete, with a leg in a cast and a beautiful adoring wife who he disdains. The change in Brick is incomprehensible to his doting father, as Brick, like many of William’s characters, keeps a shameful secret, which would otherwise be quite revelatory, closely guarded.

Brick can not forgive Maggie (or himself) for the death of Skip, his best friend. The reason for this blame is both tragic and a bit convoluted. Maggie, completely devoted to Brick, would do ANYthing for Brick. So, in an attempt to warn Brick of Skip’s personal flaws, which she fears will hurt Brick, offered herself sexually to Skip, but Skip was unable to complete the act.

The first Broadway version included implications of Skip’s homosexual attraction to Brick. Revealed by Skip to Brick the same night as Maggie’s ineffective attempt to seduce him, it was Brick’s revulsion added to Skip’s inability to complete the act with Maggie that led to Skip’s suicide.

Brick not only is furious at Maggie for trying to sleep with Skip, but more so as Brick holds Maggie responsible for proving to him Skip’s seamier nature, which reveal, Brick concludes, resulted in Skip’s suicide.

The first ending of the stage play was dark, confirming Brick’s continued rejection of his desperate wife. Maggie: “I love you Brick.” Brick: “Wouldn’t it be funny if it was true?” callously implying that she is lying for financial gain and cruelly hinting that, even were it true, ironically, he no longer loves her.

The director who Williams’ wanted for the stage play, Elia Kazan (block buster director of both stage and screen, who brought us such movies as Streetcar Named Desire, Gentlemen’s Agreement, On the Waterfront, and East of Eden), did not like this bleak ending and insisted it end on a more hopeful note. Compliantly, but reluctantly, Williams added to the second stageplay version some softening dialogue and a gesture: MAGGIE: “…nothing’s more determined than a cat on a hot tin roof, is there?” Brick allows her to touch his face implying Brick might eventually soften to her.

The third version of the story was the 1958 FILM adapted from the play, and as the most positive is the one I personally like best. The director Richard Brooks and co-author of the screenplay James Poe, made two significant changes: it eliminated the homosexual undertones and made the reconciliation between Maggie and Brick crystal clear. MAGGIE: “Thank you…for backing me up in my lie. [that she was pregnant]” BRICK: “We are through with lies and liars in this house,” as Brick smiles and locks the door.

The third version of the STAGEplay and fourth version of the story overall, was written by Williams for a 1974 revival, and combines the first two stageplay endings. Brick tells Maggie he admires her. Maggie tells Brick she loves him. Brick says: “Wouldn’t it be funny if it was true?” but then allows Maggie to touch his face, making the formerly caustic line now more one of gentle sarcasm, hinting that he has forgiven her, or at least will soon.

Gone With the Wind

This gorgeous epic of the Civil War and the resulting destruction of the genteel Southern Plantation life mostly seen from the POV of Scarlett, a feisty, largely self absorbed woman, recalls one of the most famous ending lines in cinematic history. Scarlett’s husband, Rhett, finally fed up with years of Scarlett’s neglect, emotional infidelity, manipulative personality and rejection of him, leaves. Scarlett, at long last, but too late, recognizes her love for Rhett and determines to win him back. Though she is too exhausted with the traumatic events leading up to this moment right then, she will come up with a plan the next day because: “After all – tomorrow is another day.” This line from the eponymous book published in 1936 and from the movie adaptation released in 1939 reflected an assertive, self confident, pro active and independent (even if possibly delusional) woman – quite startling in that era.

BUT that was not the original last line. The first draft of the screenplay had Scarlett passively hoping that: “Rhett! You’ll come back. I know you will.” Love Scarlett or hate her, this line would have been abysmally out of character for the strong willed, bull-headed, wrecking ball we had watched survive the multiple disasters, admittedly many self-made, which formed the structure of her life.

The far more blindly confident and dauntlessly self-assured line that ended up as the well known last line of this classic is far more in keeping with the Scarlett we had come to know.

Suspicion

Simplest and most straight forward change of heart in this group. The end of the original version of this 1948 thriller/mystery, sees Cary Grant try to murder his wife. In the revised theatrically released edition he is “only” a thief, and a repentant one at that. Reason: The studio did not want to besmirch Grant’s genial good guy image.

The Jungle Book – animated, Disney – 1967

I was 8 when this movie came out in the theater and my Dad almost assuredly took me.  As an adult and a now parent myself, one of my favorite Disney chuckles is the feminine eyes that eventually lure Mowgli away from the jungle and his animal friends and into the village – sort of an analogy for what happens to most men – leaving the less civil world of their singleness for the more gentile virtues of domesticity, beguiled by the enchantment of womanly wiles – a warning with which my husband and I enjoyed teasing our sons.

As an adult and a now parent myself, one of my favorite Disney chuckles is the feminine eyes that eventually lure Mowgli away from the jungle and his animal friends and into the village – sort of an analogy for what happens to most men – leaving the less civil world of their singleness for the more gentile virtues of domesticity, beguiled by the enchantment of womanly wiles – a warning with which my husband and I enjoyed teasing our sons.

BUT this is not the way the first draft of the story went. Leaning more on the Kipling story, there was an entire third and LONG act which might have almost doubled the time and most certainly would have made it a darker film. In the initial concept Mowgli, upon returning to the village, was at once reunited with his human mother and challenged by an elder named Buldeo who eventually forces Mowgli into the forest in search of King Louie’s treasure, but is ultimately eaten by Shere Khan who is, in turn, shot and killed by Mowgli. Mowgli is then accepted by both villagers and jungle as a full fledged member of both. Whew! Honestly a bit much, I suspect, for the young crowd for which it was originally intended.

SO – quintessential movie endings – aren’t. They are often, as Ben Franklin described the creation of both revolutions and children born out of wedlock in the musical 1776: “half-improvised and half-compromised”. Not surprising as movies are rarely made alone. Even auteurs like Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, Woody Allen, Ingmar Bergman and Kenneth Branagh must rely on a plethora of cast and crew to see their vision manifest itself into something tangible they can present to the rest of the world. As a result of: negotiation with a talent they wish to include, financial pragmatism, public relations, or just plain old common sense, story lines can be quite dynamic even as the movies are being filmed.

And it is a blessing when these serendipitous events, creative editings and pragmatic decisions end up producing the great films, like these, which grace the halls of cinematic legend.

Both the audience and he realize along the way, that if he survives his adventure, he will become the capable man and leader he otherwise would not have been.

Both the audience and he realize along the way, that if he survives his adventure, he will become the capable man and leader he otherwise would not have been.